The extraordinary life story of Hungarian painter Vilma Lwoff-Parlaghy, who portrayed Nikola Tesla and King Peter I Karađorđević

10-Jan-2026

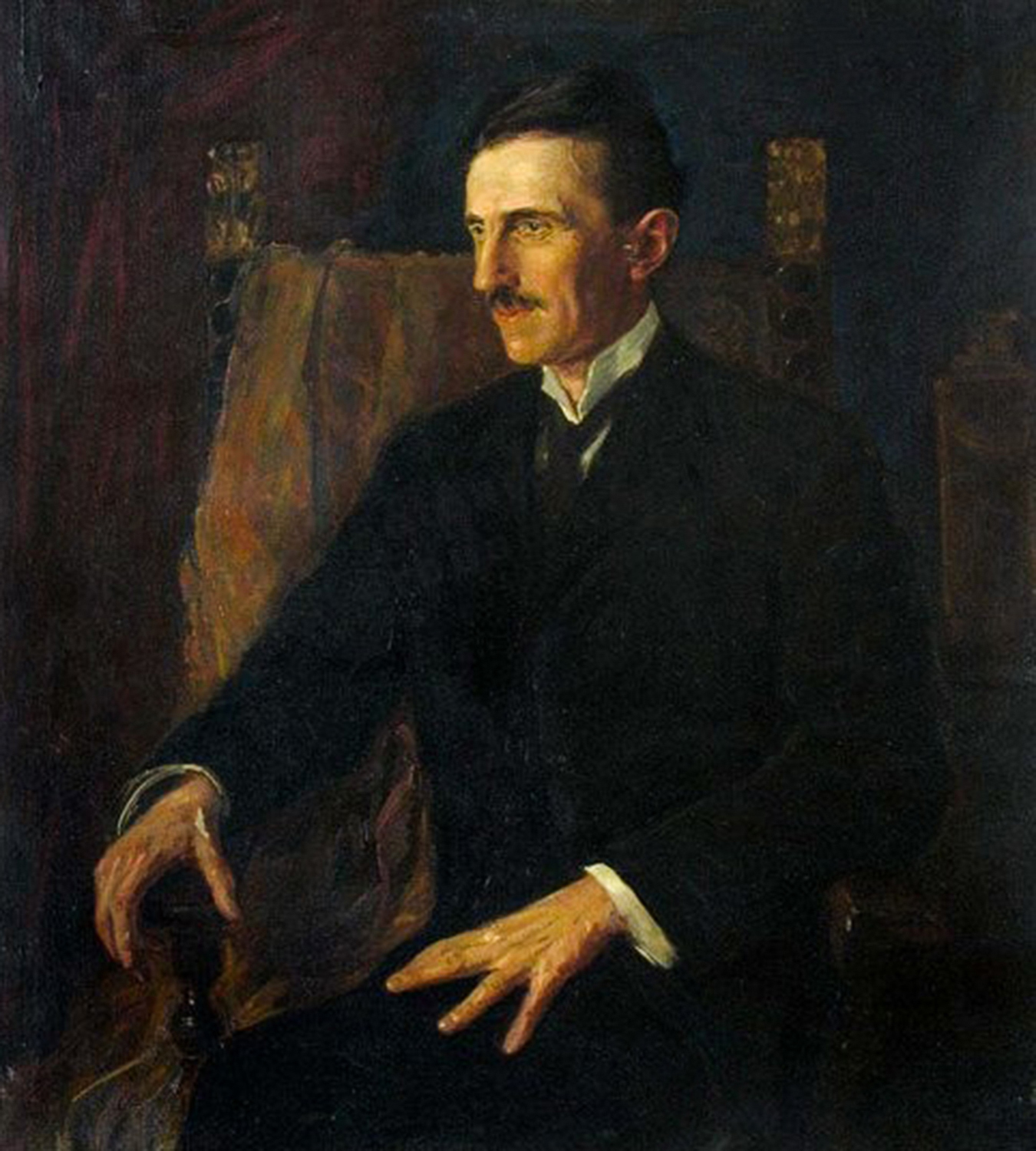

In the year when Serbia is marking the 170th anniversary of Tesla’s birth (10 July), but also the 83rd anniversary of his passing on Orthodox Christmas, we will remember the portraitist in front of whom Tesla (for the first and only time in his life) had sat. Due to this, along with his image in old photographs, we can also evoke his life through the artwork of the Hungarian painter Vilma Lwoff-Parlaghy.

However, while this world-renowned artist had painted over 120 portraits of prominent Americans and Europeans from 1884 to 1923, including a portrait of Serbian King Peter I Karađorđević, she has remained relatively unknown to the Serbian public.

Leading US magazines and newspapers, from the New York Times, the New York Evening Telegraph, the New York Herald, and the City Journal to Form Magazine, have written extensively about her. They described her physical appearance as graceful and striking, also noting that she was full of life and a very entertaining conversationalist.

She has an unusual life story. Born in 1863 in eastern Hungary, she died in New York City on 28 August 1923. While studying in Budapest, her talent for drawing was perceived early on, and her family sent her to study in Paris, where her portraiture skills were particularly distinguished. She perfected her art education first in Paris and later on in Munich.

Not long after, Wilma opened her own studio in Berlin, bringing together European aristocracy and prominent members of society. In fact, a portrait of her mother attracted public attention in Berlin in 1890.

Vilma Lwoff-Parlaghy also painted a portrait of King Peter I Karađorđević at the end of 1903, where the king can be seen standing in front of the portraitist in the Konak Palace in Belgrade. A foreign photographer happened to be in Belgrade on 8 November 1903 to chronicle this modelling, and therefore his photo was published in the magazine L’Illustrazione Italiana on 20 December 1903. Today, we can see it online and purchase it for US $150 or 450 (the price varies depending on the resolution).

Collateral for bills outstanding

Afterwards, Vilma painted Tesla’s portrait in New York City. The scientist, according to some of his biographers, had sat patiently in front of his friend and artist under electric lights of his own design. The lights were filtered through blue glass, emulating the northern lights. Tesla posed in her studio at 109 East 39th Street, Park Avenue, where the artist moved in 1916. This work, known as the Blue Portrait, is the only portrayal of Tesla and the painting has acquired a cult status – after being lost for years. The original portrait is in the German city of Husum, in the Nordsee Museum, and until 2009 it was listed in the museum’s collection as Portrait of an Unknown Man.

Vilma Lwoff-Parlaghy first visited New York City in 1896, and three years later she married the Russian Prince Georgy Lwoff in Prague. Although they divorced quickly, she continued to call herself Princess Lwoff-Parlaghy, which served as good publicity for the sale of her paintings. She used this title with the permission of her ex-husband, Prince Lwoff, who continued to send her an annual allowance even after the divorce. She divorced the prince in 1903, telling the press that he was too ‘naughty’ for her.

She settled permanently in Manhattan in June 1908, taking up residence in a thirteen-room suite on the 3rd floor of the Plaza Hotel, overlooking Central Park, bringing with her a large entourage. There she entertained New York society, in rooms decorated with Old Master paintings, tapestries, and antiques.

She told reporters that she intended to paint a hundred of the most prominent American men, and consequently, they proceeded to arrive at her luxurious studio to sit for her.

In addition to the apartments and studios in the aforementioned hotel, the princess also had a mountain cottage and spent her summers at her villa on the Riviera. However, her luxurious lifestyle began to disappear when World War I broke out in Europe, and requests for portraits dwindled. Her wealth slowly dissipated from 1914, and soon after, due to outstanding bills, she began to be pursued by lawyers, bankers and the owners of the stables where she kept her horses.

The hotel management asked her to leave the Plaza, and her paintings were held as collateral for bills outstanding. A New York diamond dealer from Brooklyn lent her $12,000 to buy a so-called row house on East 39th Street, where she continued to paint and entertain, albeit on much smaller premises.

Highly priced portraits

She celebrated her 60th birthday (15 April 1923) with an exhibition she called the Manhattan Hall of Fame in the Carlton Hotel on Madison Avenue.

Three friends of Mikhail Idvorsky Pupin also sat in front of her easel – the inventor and businessman Thomas Edison, the president of Columbia University Seth Lowe, and one of the richest Americans, Andrew Carnegie. Also modelling for her were the Queen of Belgium, the Shah of Persia, Chancellor von Bismarck, a businessman who financed the construction of the New York subway, Kaiser Wilhelm II, Theodore Roosevelt, as well as numerous fellow painters and sculptors.

The market value of Princess Lwoff-Parlaghy’s portraits reached $7,000, which was an extremely high price at the time. She received numerous awards for her work, including gold medals at exhibitions in Berlin, Vienna, Paris, etc. and at the Chicago-based World’s Columbian Exposition in 1893, when all the exhibition pavilions were lit by 12 Tesla two-phase generators (while at the same time Tesla’s great victory over Edison took place). Vilma Lwoff-Parlaghy also exhibited in the “Women’s Pavilion” at the World’s Columbian Exposition, when she was awarded.

However, Lady Luck definitely abandoned her in 1923. At the end of August, a New York deputy sheriff came to her door with warrants seizing her property in order to settle various mortgages, and then discovered that she had passed away. She was only 60 years old when she left this world, surrounded by her unsold works of art, a physician and a devoted maid, as well as a long line of creditors waiting outside her door. An auction of her estate was held in New York in April 1924, and over 350 valuable items were auctioned.

She was buried at Woodlawn Cemetery in the Bronx, where Mikhail Idvorsky Pupin, his wife Katarina Sara, and daughter Varvara are also buried.

The New York Times, 2 March 1916

The website of the Tesla Memorial Society of New York features an article from the New York Times dated 2 March 1916, reporting on a reception given by Princess Lwoff-Parlaghy, at which Nikola Tesla’s Blue Portrait was exhibited for the first time in her New York studio.

The journalist wrote that one of Mr. Tesla’s beliefs was that there was something inauspicious about sitting for a portrait, which was why he had never agreed to do it until he entered the princess’s studio.

On that occasion, Mr. Tesla first solved the lighting problem, then sat down in an armchair, and began to contemplate the universe. He sat for hours, oblivious to his surroundings. Thus, the painter managed to create a figure whereupon there was no evidence that the sitter was aware of anyone even watching him, let alone studying his facial features from the other side of the easel.

Like so, both the scientist and the artist were lost in their work, their thoughts and dreams.

Source: Мarina Bulatović, Politika daily, Arts and Culture section